The University of Alabama Press

Two new books in the Modern and Contemporary Poetry Series40% Discount on Newest MCP Titles

http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/bernstein/blog/archive/U-AL-2009.html

for discount details, tables of content, covers, etc.

The University of Alabama Press

Two new books in the Modern and Contemporary Poetry SeriesIn Scribe, his seventh book of poetry, published this fall, Norman Finkelstein (the poet, not the Israel critic) works the contradictions of being a Jew. He is simultaneously secular and religious, stately and conversational, prophetic, and circumspect.

To begin with: Finkelstein is keenly aware of the theological implications of Judaism. In a article in the academic journal Shofar, the poet and critic Alicia Ostriker claims that contemporary American Jewish poets seek holiness “not in the disembodied God but in the physical world.” This might be true of many Jewish poets, but not of Finkelstein. The man invokes a very Jewish—because absolutely disembodied—God, as in the poem “Desert”:

Neither upon the sky nor upon the ground

Neither in the desert nor at the mountain

Neither in the heights nor in the depths

Neither present nor absent

Neither known nor unknown

Neither strange nor familiar

Neither whole nor in fragments

Neither revealed nor hidden

Neither sacred nor profane

Neither spoken nor silent.

While it might sound like mysticism, it is pure, rational Maimonides who tells us that every time we try to nail God down in our own, too human terms, we increase our distance from Him. Finkelstein keeps Him in the realm of the divine, represented as the space between contradictions.

When Finkelstein turns from the attributes of God to our own imperfections in the poem “Scribe,” he has no trouble enlisting the cadence of the prophets:

You have heeded the word of the outside god

and you have heeded the word of no god at all,

like a prophet turned archaeologist

a scribe turned into a scribe.

This is pretty harsh stuff. Finkelstein charges us with having foresworn the future by chasing false gods or—just as bad—chasing no god at all. We have turned prophecy into nostalgia and turned our holy scribes into scribblers, the guilty transcribers of a not quite forgotten past.

Finkelstein teeters on the edge of a thumping sanctimoniousness, but he is saved from the brink here by the fact that he is indicting himself as much as he is chastising the tribes of Jeshurun, perhaps even more so. He has no other choice. God is too far away and Finkelstein has appeared too late in history for faith. This hardly presents a vista for hope and certainly not one for redemption. But Finkelstein’s work has no trouble freely espousing both a secularized recuperation of religion as well a religious approach to the secular.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Scribe is a series of poems based on a seemingly unlikely muse: architect Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language, a gently polemical attempt to realign architecture and city planning with a very generous notion of human need. But Alexander describes architecture in terms of poetry, seeing in them both opportunities for physical, linguistic, and emotional fulfillment. Finkelstein, whose poems often engage the space of the whole page, sees poetry in terms of architecture. More importantly, Alexander places great stock in the imagination. He claims that a home, like a city, needs its private spaces and its dreams. “Make a place in the house,” he writes, “which is locked and secret.” There, “the archives of the house, or more potent secrets, might be kept.”

Finkelstein’s secular midrash allows him to use a bedroom to reflect on his own psyche, his love and his poetry at the same time, as in “Children’s Realm”:

I want it so within myself

and within those I love—

a continuum of spaces

where the child at play

may pass by or enter

that place common to all

of my being

Nor can it be

too far from that grown-up world

also of bodies and minds

of storms and of the peace after storms

the child and adult facing each other

across a space that is all

terror and enchantment.

You can hear a kind of meditative stateliness (the archaism of that “so” ) which goes with the biblical repetitiveness (“storms and the peace after storms”). All this leads to that quiet little bang at the end, the magical face-off between generations.

There is a payoff to his use of Alexander’s book. “Sacred Sites/Holy Ground” stands at the imaginative center of Finkelstein’s topography of a radically transformed world. In it, he quotes Alexander’s call for “SACRED SITES.” Like Alexander, Finkelstein does not name these sites nor does he specify the exact nature of their sanctity, beyond the fact that laws should afford them permanent protection: “OUR ROOTS/IN THE VISIBLE SURROUNDINGS/CANNOT BE VIOLATED.” Our roots in a visible landscape—not in divine sanction; these are utopian, not overtly religious places.

The suggestive relation between Finkelstein’s vision of a fulfilled life and redemption is telling. Redemption remains a promise while utopia remains a hope. These days, they are both the stuff of chastened prophecy and skeptical exhortation. But according to Finkelstein, they both are necessary if our scribblers are to transform themselves into scribes.

***

It doesn’t seem quite fair to talk about Natalie Lyalin’s Pink & Hot Pink Habitat and dwell on the fact that she was born in Russia. But it is unavoidable. She herself says that “the immigration experience has been a great and interesting rift in my life. I think that kind of upheaval is great psychological material for writing poems.” That rift shows up in her poems in a number of ways.

Like much contemporary poetry her work is disjunctive. In “Jeffrey Bloodhound Sans” she writes:

Girl words. A tomato. A plum. An apricot.

Time is holding in a clear tube.

Time is lightning on a spare key.

Words that do not yet exist. Alibubo. Bubsigtree. Grivstalbikt.

But these disjunctions are not just examples of a period style. They express deep dislocations—linguistic, physical and psychological.

Language first: it’s hard not to view her flights of linguistic fancy as the result of having to live between languages. Memories of Russian come up when she imitates her father’s voice: “Feel this here pain” and “Whatever happened at prom?” Speakers of Slavic languages have a miserable time with definite articles as well as finding the right place for adjectives and adverbs.

When it comes to syntax, English is also remarkably simple compared to Russian, German, and a host of other languages. But English hammers non-native speakers with the number and complexity of its idioms. The freedom to get idioms wrong, to discover new connections, even to make up words that do not yet exist, is miserable for an immigrant, but a real gift for a poet.

Nevertheless, dislocation has its costs:

Your family is in flight. It seems that decades didn’t happen or happened all at once. The next few years are all weddings. On the end of holidays we wait for the next holiday. We remember bombed out resorts and the constant cigarettes.

(“Opalescent”)

Lyalin the poet cannot distance herself from the confusions of memory. She might begin as a “you” but ends up inevitably with a “we.”

Pink & Hot Pink Habitat is not a particularly grim book, although for all its surface play, it is a very serious one. Lyalin has probably earned the right to express real doubt: “They promise that G-d is not vengeful,/ but do they really know that.” But by the same token, doubt also lends weight to passages like this:

Humans are G-d’s secret architecture and your mother is the cupola of maple leaves. I have put myself here, in this orb of muscle and wonderment, grain, gold silk and the map of roads.

(“Dune and Swale”)

Muscle and wonderment. If nothing else, a good prescription for Jewish poems.

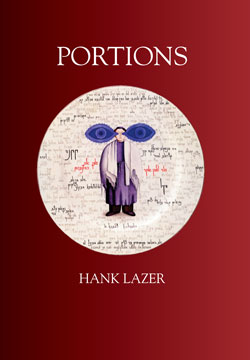

Hank Lazer's Portions is a gem. Based on a gematria-like numerical formula combined with the notion of the parshah, the portion of Torah read weekly in the synagogue, these poems are elegant, profound and perfectly direct. With their short, telegraphic lines and Jewish sense of the inextricability of the immanent and the transcendent, they carry the tradition forward and make it new.

Hank Lazer's Portions is a gem. Based on a gematria-like numerical formula combined with the notion of the parshah, the portion of Torah read weekly in the synagogue, these poems are elegant, profound and perfectly direct. With their short, telegraphic lines and Jewish sense of the inextricability of the immanent and the transcendent, they carry the tradition forward and make it new.SHOFAR

Vol. 27, NO. 3

Articles

Partisan Experiments: Communism, Poetry, and the Liberal Imagination,

1934-1940

Ethan Goffman........................................................................................................ 4

"Time to Translate Modernism into a Contemporary Idiom": Pedagogy,

Poetics, and Bob Perelman's Pound

Alan Golding.......................................................................................................... 16

Tracking the Word: Judaism's Exile and the Writerly Poetics of George

Oppen, Armand Schwerner, Michael Heller, and Norman Finkelstein

Burt Kimmelman.................................................................................................. 30

Jewish Counterfactualism in Recent American Poetry

Joshua Schuster................................................................................................... 52

Is There a Distinctive Jewish Poetics? Several? Many? Is There Any

Question?

HankLazer............................................................................................................. 72

A Portfolio of Poems

poetry and translations by Charles Bernstein and Kevin M. F. Platt, David

Epstein, Thomas Fink, Norman Finkelstein, Benjamin Friedlander, Arielle

Greenberg, Jamey Hecht, Michael Heller, Alan Holder, Burt Kimmelman,

Joseph Lease, Deena Linett, Bonnie Lyons, Stephen Paul Miller, Daniel

Morris, Alicia Ostriker, Warren Rosenberg, Steven P. Schneider, Daniel R.

Schwarz, Nikki Stiller, William Wallis, and Henry Weinfield........................ 91

Review Essays

American Jewish Poetry, Familiar and Strange Alicia Ostriker....148

Passing Through

Henry Weinfield.................................................................................................. 151

Book Reviews......................................................................... 156

Book Notes........................................................................... ...213

“The house is dark in the February damp, but when she opens the door to let me in, Imm Nizar is laughing.”

Stop, just a moment, to appreciate that sentence from My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness. Start with the pacing: three poised clauses, sight and touch yielding to motion, then sound. Savor how it’s knit by sound, as “dark” sets up “damp,” then “door,” then “Nizar,” in” modulates to “Imm,” and “damp” transforms into “laughing.” Most of all, thank Adina Hoffman, its author, for the way it beckons you into the daunting subject announced by her subtitle: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century. At the start of what she claims is the first biography of a Palestinian writer “in any language (including Arabic),” Hoffman calls up laughter, not anger, hospitality, not guilt, and a domestic scene instead of the public saga of displacement, frustration, and war.

The poet she focuses on is an unlikely subject: the gracious, self-deprecating husband of Imm Nizar, eighty-seven-year old Taha Muhammad Ali. Given the fame he has recently accrued, reading with his translator, Peter Cole, to hundreds, sometimes thousands of fans at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival, Muhammad Ali may be better known in English now than he is in Arabic. Born in 1931, he didn’t write a poem until the early 1970s, by which time Samih al-Qasim and Mahmoud Darwish, the two other poets I will discuss, were famous as rock stars. “How is it that we didn’t even know you existed?” the Iraqi author Buland al-Haydari demanded of Muhammad Ali a generation later. The explanation was simple enough: When they met at his first international reading, the poet had no political ties to make him famous, little distribution for his work, and, at fifty-seven years old, still only one slim volume to his name.

In centering her “group portrait” of Palestinian writers around a poet even she calls “marginal,” Hoffman borrows a strategy from the poet himself. “Taha has often likened his own poetic method to what he calls in English ‘bill-i-ar-des,’” she writes. “‘You aim over here—‘ a long, gnarled, yet delicately mottled farmer’s finger points to the right—‘to strike over there.’ The finger bends sharply to the left.” To use the technical term, both Muhammad Ali and Hoffman put considerable “English” on the course of Palestinian history since the 1930s, spinning it into useful, graceful, surprising trajectories. As a result, My Happiness Bears No Resemblance to Happiness offers the best introduction I know, not only to the poet at its heart, but also to the more famous authors who have crossed paths with him or spent years talking to him in the makeshift, under-the-radar salon of his souvenir shop in Nazareth. With it in hand, I have spent the past few months re-reading not only Muhammad Ali’s own work, but also Sadder Than Water, the recent Selected Poems from Samih al-Qasim (another Ibis Editions poet, in English) and, with blossoming admiration, the fine new crop of Darwish translations, which let American readers grapple, for the first time, with complete books by this expansive, reflective, mercurial, and self-revising poet. Not to slight the useful pair of monolingual Selecteds, The Adam of Two Edens (2000) and Unfortunately, It Was Paradise (2003), translated by various hands, but for Darwish, as we shall see, the collection was as much the unit of composition as the individual poem. Only now, thanks to translators Jeffrey Sacks and Fady Joudah, can readers without Arabic, including me, begin to take his measure.

a third volume (although it's a sort of prequel) of the Poems for the Millennium anthology series, this one a book of "Romantic and Postromantic Poetry." You can read through the table of contents here, and as you'll see, it's a pretty wonderful gathering, the sort of book I won't just take on in the classroom (as I have the previous volumes), but will also read by myself, for pleasure, and as a reminder of what poetry promised me when we both (alas!) were young.

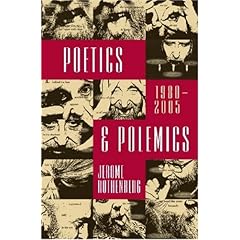

a third volume (although it's a sort of prequel) of the Poems for the Millennium anthology series, this one a book of "Romantic and Postromantic Poetry." You can read through the table of contents here, and as you'll see, it's a pretty wonderful gathering, the sort of book I won't just take on in the classroom (as I have the previous volumes), but will also read by myself, for pleasure, and as a reminder of what poetry promised me when we both (alas!) were young. Poetics and Polemics: 1980-2005, a collection of essays, commentaries, interviews, etc., which will be as rich a resource as anyone interested in Jewish poetry could ask.

Poetics and Polemics: 1980-2005, a collection of essays, commentaries, interviews, etc., which will be as rich a resource as anyone interested in Jewish poetry could ask.My father was a god and did not know it. He gave me

The Ten Commandments neither in thunder nor in furry; neither in fire nor in cloud

But rather in gentleness and love. And he added caresses and kind words

and he added “I beg You,” and “please.”

And he sang “keep” and “remember” the Shabbat

In a single melody and he pleaded and

cried quietly between one utterance and the next ,

“Do not take the name of God in vain,” do not take it, not in vain,

I beg you, “do not bear false witness against your neighbor.”

And he hugged me tightly and whispered in my ear

“Do not steal. Do not commit adultery. Do not murder.”

And he put the palms of his open hands

On my head with the Yom Kippur blessing.

“Honor, love, in order that your days might be long

On the earth.” And my father’s voice was white like the hair on his head.

Later on he turned his face to me one last time

Like on the day when he died in my arms and said

I want to add Two to the Ten Commandments:

The eleventh commandment – “Thou shall not change.”

And the twelfth commandment – “Thou must surely change.”

So said my father and then he turned from me and walked off

Disappearing into his strange distances.

Allen Grossman, one of the most important figures in the field of Jewish American poetry and poetics, has been awarded the Bollingen Prize. Here are the details. And here (scroll down) are three poems from Descartes' Loneliness. Congratulations, Allen, from the Big Jewish Blog.

The Jewish poet (the Jew's great poet whom I wish speculatively to summon to mind) is called monologically by Presence itself. The correlative but severely contrastive figure in traditional Jewish narrative to the gentile muse (daughter of Memory) is the Shechinah, whose name means dwelling--the dwelling of the name in the world: the Jew's place to be.

Allen Grossman,

"Jewish Poetry Considered as a Theophoric Project"