Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Busy, Busy!

To give you all something to tide you over, here's a link to the review I wrote for Shofar of Michael Heller's wonderful collection of essays, Uncertain Poetries. It hasn't come out in print yet, evidently, but they've posted the full text to their website, so go read it there!

My kids like this--enjoy--

More soon,

E

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

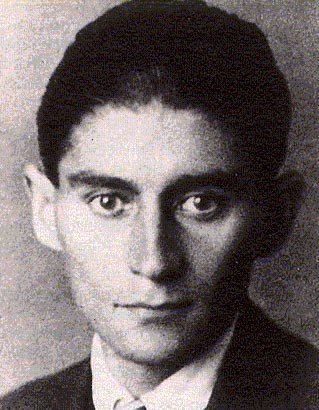

Kafka

Teaching The Metamorphosis tonight. Well, not teaching it, exactly: talking about it with adult readers at the Wilmette Public Library, where I am leading discussions for a "Let's Talk About It: Jewish Literature" series sponsored by Nextbook. We're doing the Jewish Tales of the Supernatural sequence--they choose the books, I just talk about them!--and it's already been something of an education for me.

Teaching The Metamorphosis tonight. Well, not teaching it, exactly: talking about it with adult readers at the Wilmette Public Library, where I am leading discussions for a "Let's Talk About It: Jewish Literature" series sponsored by Nextbook. We're doing the Jewish Tales of the Supernatural sequence--they choose the books, I just talk about them!--and it's already been something of an education for me.My favorite book in the series so far has been S. Y. Ansky's play The Dybbuk, which is utterly wonderful; two books from now we'll do another play, Kushner's Angels in America, which I've taught a half-dozen times and love more the more I read it. Singer's Satan in Goray? Bleak, but brilliant, or maybe brilliant but bleak. Next month: The Puttermesser Papers. I really didn't like that one. Really, really didn't like it. (What Ozick do I like? Not much comes to mind. Anyone out there able to make the pitch, close the deal? I have a month. Help me, somebody!)

Kafka? Meh. Not a writer I love. I'm too optimistic, too happy, too American (perhaps) to feel that way, although I did my best to love him at 16 and 17. (Never could pull off that broody, angsty thing.) Still, he's not a writer I actively dislike, either, and I am actually rather proud of the take-home questions we handed out last month to prepare for tonight.

I'm off to reread the text itself--not much of the criticism satisfies me just now, so let me pass those questions along and pat myself on the back for posting something today.

Here they are: steal at will!

1) Unlike the first two books in this series, Satan in Goray and The Dybbuk, Kafka’s Metamorphosis does not explicitly deal with Jewish characters or Jewish subjects. What might be gained or lost by reading the book as a Jewish novel? How does it seem different if we read it this way, rather than as a Modernist or Central European text?

2) Readers who approach The Metamorphosis as a Jewish book often refer to one or both of the following passages from Kafka’s letters:

“Most young Jews who began to write German wanted to leave Jewishness behind them, and their fathers approved of this, but vaguely (this vagueness was what was so outrageous to them). But with their posterior legs they were still glued to their fathers' Jewishness and with their waving anterior legs they found no new ground. The ensuing despair became their inspiration. . . . The product of their despair became their inspiration. . . . The product of their despair could not be German literature, though outwardly it seemed to be so. They existed among three impossibilities, which I just happen to call linguistic impossibilities. . . . These are: the impossibility of not writing, the impossibility of writing German, the impossibility of writing differently. One might also add a fourth impossibility, the impossibility of writing. . . . “

"The disgusting shame of perennially living under protection. Is it not self-evident that one should leave where one is hated so much? (Zionism or ethnic feeling is not even needed here.) The heroism of staying under these conditions is that of cockroaches in the bathroom one cannot get rid of.”

3) Historian Gershom Scholem once wrote his friend Walter Benjamin that “I advise you to begin any inquiry into Kafka with the Book of Job, or at least with a discussion of the possibility of divine judgment, which I regard as the sole subject of Kafka’s production.” Benjamin took a different view, and wrote that “the most essential point about Kafka is his humor…. I believe someone who tried to see the humorous side of Jewish theology would have the key to Kafka.” Do either of these suggestions help us read The Metamorphosis? Is there any way to understand the book as concerned with divine judgment? Is it theological in a particularly Jewish or humorous way?

4) The Metamorphosis begins with Gregor’s transformation, and ends with a focus on his sister Grete. How does Kafka’s portrayal of Grete compare with Singer’s and Ansky’s treatment of female characters in Satan in Goray and The Dybbuk? Why might the novel end with a focus on her, rather than on her brother?

Saturday, November 03, 2007

Multilingual Jewish Literature and Multicultural America

And just for a little forshpaytz, here's a discussion of a poem by Harvey Shapiro--a bit of my "Ghosts of Yiddish in American Avant-Garde Poetry":

Consider, for instance, Harvey Shapiro’s poem “For the Yiddish Singers in the Lakewood Hotels of My Childhood”:

I don't want to be sheltered here.

I don't want to keep crawling back

To this page, saying to myself,

This is what I have.

I never wanted to make

Sentimental music in the Brill Building.

It's not the voice of Frank Sinatra

I hear.

To be a Jew in Manhattan

Doesn't have to be this.

These lights flung like farfel.

These golden girls.

Shapiro was born in 1924. During his childhood, Lakewood, New Jersey was a well-established Jewish winter resort. In the 1890s, when a leading gentile hotel had turned away the department store magnate Nathan Straus because he was Jewish, Straus “promptly built next to it a hotel, twice as large, for Jews only. In a few years other Lakewood hotels sold out to Jewish operators, and kosher establishments multiplied on all sides” (Higham 243). In the heymish Lakewood hotels, like those of the Catskills, one could still hear Old World Yiddish entertainers, along with more contemporary American popular music of the sort produced by Jewish American songwriters working out of the Brill Building, a Manhattan center of the music industry from the thirties through the sixties. Yet whether the “sentimental music” is sung in Yiddish by Jewish singers in Lakewood or in English by Frank Sinatra, crooning a hit written by Jewish American song smiths, Shapiro still feels trapped in memory, ironically “sheltered” by his past and continually “crawling back” to the page on which he inscribes his early history.

A proof text: in Portnoy’s Complaint, it is to a Lakewood hotel that the young Alex Portnoy is taken on a weekend vacation with his parents and their Gin Rummy club, and Alex is given a taste of nature and its poetry, walking with his hardworking, semi-literate, constipated father and breathing “Good winter piney air” (Roth 29). The phrase in Shapiro’s poem, “crawling back,” connotes both defeat and infantilization, a problem, of course, that haunts Portnoy as well. The poet asserts that “To be Jew in Manhattan / Doesn’t have to be this,” but everything in the poem indicates otherwise.

What, we must ask, is another way to be a Jew in Manhattan—and more specifically, an adult male Jew? The obvious answer has to do with the last line of the poem, not even a sentence but a descriptive assertion, a finger pointing at a new world of possibility: “These golden girls”: shiksa goddesses of the type Portnoy also perpetually pursues. Farewell, Lakewood and its Yiddish singers; welcome, the sexual conquests of the fully assimilated, cosmopolitan Manhattanite. But wait: it is the penultimate line on which the poem turns. Looking down on the city at night, dreaming of love, does the poet see the Great White Way? No, he sees “These lights flung like farfel.” Farfel? Farfel: “Yiddish, from Middle High German varveln; small pellet-shaped noodles, made of either flour mixed with egg or matzo. Farfel is most prevalent in Jewish cuisine, where it is a seasonal item used in Passover dishes.” Those golden girls, those city lights, shine, in the poet’s imagination, like Mama’s cooking on Pesach. This, then, is to be a Jew in Manhattan, haunted by the Yiddish language and the Yiddish past.